Πώς θα κριθεί ο κόσμος (ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΝ 25)

Πώς θα κριθεί ο κόσμος 31«Όταν θα έρθει ο Υιός του Ανθρώπου με όλη του τη μεγαλοπρέπεια και θα τον συνοδεύουν όλοι οι άγιοι άγγελοι, θα καθίσει στο βασιλικό θρόνο του. 32Τότε θα συναχθούν μπροστά του όλα τα έθνη, και θα τους ξεχωρίσει όπως ξεχωρίζει ο βοσκός τα πρόβατα από τα κατσίκια. 33Τα πρόβατα θα τα τοποθετήσει στα δεξιά του και τα κατσίκια στ’ αριστερά του. 34Θα πει τότε ο βασιλιάς σ’ αυτούς που βρίσκονται δεξιά του: “ελάτε, οι ευλογημένοι απ’ τον Πατέρα μου, κληρονομήστε τη βασιλεία που σας έχει ετοιμαστεί απ’ την αρχή του κόσμου. 35Γιατί, πείνασα και μου δώσατε να φάω, δίψασα και μου δώσατε να πιω, ήμουν ξένος και με περιμαζέψατε, 36γυμνός και με ντύσατε, άρρωστος και μ’ επισκεφθήκατε, φυλακισμένος κι ήρθατε να με δείτε”. 37Τότε θα του απαντήσουν οι άνθρωποι του Θεού: “Κύριε, πότε σε είδαμε να πεινάς και σε θρέψαμε ή να διψάς και σου δώσαμε να πιεις; 38Πότε σε είδαμε ξένον και σε περιμαζέψαμε ή γυμνόν και σε ντύσαμε; 39Πότε σε είδαμε άρρωστον ή φυλακισμένον κι ήρθαμε να σε επισκεφθούμε;” 40Τότε θα τους απαντήσει ο βασιλιάς: “σας βεβαιώνω πως αφού τα κάνατε αυτά για έναν από τους άσημους αδερφούς μου, τα κάνατε για μένα”. 41»Ύστερα θα πει και σ’ αυτούς που βρίσκονται αριστερά του: “φύγετε από μπροστά μου, καταραμένοι· πηγαίνετε στην αιώνια φωτιά, που έχει ετοιμαστεί για το διάβολο και τους δικούς του. 42Γιατί, πείνασα και δε μου δώσατε να φάω, δίψασα και δε μου δώσατε να πιω, 43ήμουν ξένος και δε με περιμαζέψατε, γυμνός και δε με ντύσατε, άρρωστος και φυλακισμένος και δεν ήρθατε να με δείτε”. 44Τότε θα του απαντήσουν κι αυτοί: “Κύριε, πότε σε είδαμε πεινασμένον ή διψασμένον ή ξένον ή γυμνόν ή άρρωστον ή φυλακισμένον και δε σε υπηρετήσαμε;” 45Και θα τους απαντήσει: “σας βεβαιώνω πως αφού δεν τα κάνατε αυτά για έναν από αυτούς τους άσημους αδερφούς μου, δεν τα κάνατε ούτε για μένα”. 46Αυτοί λοιπόν θα πάνε στην αιώνια τιμωρία, ενώ οι δίκαιοι στην αιώνια ζωή».

ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΝ 25, Η Αγία Γραφή (Παλαιά και Καινή Διαθήκη) (TGV) | The Bible App

Η παραβολή των ταλάντων (ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΤΘΑΙΟΝ 25)

Η παραβολή των ταλάντων (Λκ 19:11-27) 14«Η βασιλεία του Θεού μοιάζει μ’ έναν άνθρωπο ο οποίος φεύγοντας για ταξίδι, κάλεσε τους δούλους του και τους εμπιστεύτηκε τα υπάρχοντά του. 15Σ’ άλλον έδωσε πέντε τάλαντα, σ’ άλλον δύο, σ’ άλλον ένα, στον καθένα ανάλογα με την ικανότητά του, κι έφυγε αμέσως για το ταξίδι. 16Αυτός που έλαβε τα πέντε τάλαντα, πήγε και τα εκμεταλλεύτηκε και κέρδισε άλλα πέντε. 17Κι αυτός που έλαβε τα δύο τάλαντα, κέρδισε επίσης άλλα δύο. 18Εκείνος όμως που έλαβε το ένα τάλαντο, πήγε κι έσκαψε στη γη και έκρυψε τα χρήματα του κυρίου του. 19»Ύστερα από ένα μεγάλο χρονικό διάστημα, γύρισε ο κύριος εκείνων των δούλων και έκανε λογαριασμό μαζί τους. 20Παρουσιάστηκε τότε εκείνος που είχε λάβει τα πέντε τάλαντα και του έφερε άλλα πέντε. “Κύριε”, του λέει, “μου εμπιστεύτηκες πέντε τάλαντα· κοίτα, κέρδισα μ’ αυτά άλλα πέντε”. 21Ο κύριός του τού είπε: “εύγε, καλέ και έμπιστε δούλε! Αποδείχτηκες αξιόπιστος στα λίγα, γι’ αυτό θα σου εμπιστευτώ πολλά. Έλα να γιορτάσεις μαζί μου”. 22Παρουσιάστηκε κι ο άλλος με τα δύο τάλαντα και του είπε: “κύριε, μου εμπιστεύτηκες δύο τάλαντα· κοίτα, κέρδισα άλλα δύο”. 23Του είπε ο κύριός του: “εύγε, καλέ και έμπιστε δούλε! Αποδείχτηκες αξιόπιστος στα λίγα, γι’ αυτό θα σου εμπιστευτώ πολλά. Έλα να γιορτάσεις μαζί μου”. 24Παρουσιάστηκε κι εκείνος που είχε λάβει το ένα τάλαντο και του είπε: “κύριε, ήξερα πως είσαι σκληρός άνθρωπος. Θερίζεις εκεί όπου δεν έσπειρες και συνάζεις καρπούς εκεί που δε φύτεψες. 25Γι’ αυτό φοβήθηκα και πήγα κι έκρυψα το τάλαντό σου στη γη. Ορίστε τα λεφτά σου”. 26Ο κύριός του τού αποκρίθηκε: “δούλε κακέ και οκνηρέ, ήξερες πως θερίζω όπου δεν έσπειρα, και συνάζω καρπούς απ’ όπου δε φύτεψα! 27Τότε έπρεπε να βάλεις τα χρήματά μου στην τράπεζα, κι εγώ όταν θα γυρνούσα πίσω, θα τα έπαιρνα με τόκο. 28Πάρτε του, λοιπόν, το τάλαντο και δώστε το σ’ αυτόν που έχει τα δέκα τάλαντα. 29Γιατί σε καθέναν που έχει, θα του δοθεί με το παραπάνω και θα ’χει περίσσευμα· ενώ απ’ όποιον δεν έχει, θα του πάρουν και τα λίγα που έχει. 30Κι αυτόν τον άχρηστο δούλο πετάξτε τον έξω στο σκοτάδι. Εκεί θα κλαίνε, και θα τρίζουν τα δόντια”».

What Is the Torah?

by Ariela Pelaia Updated April 04, 2019

The Torah, Judaism’s most important text, consists of the first five books of the Tanakh (also known as the Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses), the Hebrew Bible. These five books—which include the 613 commandments (mitzvot) and the Ten Commandments—also comprise the first five books of the Christian Bible. The word “Torah” means “to teach.” In traditional teaching, the Torah is said to be the revelation of God, given to Moses and written down by him. It is the document that contains all of the rules by which the Jewish people structure their spiritual lives.

Fast Facts: The Torah

- The Torah is made up of the first five books of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible. It describes the creation of the world and the early history of the Israelites.

- The first full draft of the Torah is believed to have been completed in the 7th or 6th century BCE. The text was revised by various authors over subsequent centuries.

- The Torah consists of 304,805 Hebrew letters.

The writings of the Torah are the most important part of the Tanakh, which also contains 39 other important Jewish texts. The word “Tanakh” is actually an acronym. “T” is for Torah (“Teaching”), “N” is for Nevi’im (“Prophets”) and “K” is for Ketuvim (“Writings”). Sometimes the word “Torah” is used to describe the entire Hebrew Bible.

Traditionally, each synagogue has a copy of the Torah written on a scroll that is wound around two wooden poles. This is known as a Sefer Torah and it is handwritten by a sofer (scribe) who must copy the text perfectly. In modern printed form, the Torah is usually called a Chumash, which comes from the Hebrew word for the number five.

Books of the Torah

The five books of the Torah begin with the creation of the world and end with the death of Moses. In Hebrew, the name of each book is derived from the first unique word or phrase that appears in that book.

Genesis (Bereshit)

Bereshit is Hebrew for “in the beginning.” This book describes the creation of the world, the creation of the first humans (Adam and Eve), the fall of mankind, and the lives of Judaism’s early patriarchs and matriarchs (the generations of Adam). The God of Genesis is a vengeful one; in this book, he punishes humanity with a great flood and destroys the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. The book ends with Joseph, the son of Jacob and the grandson of Isaac, being sold into slavery in Egypt.

Exodus (Shemot)

Shemot means “names” in Hebrew. This, the second book of the Torah, tells the story of the Israelites’ bondage in Egypt, their liberation by the prophet Moses, their journey to Mount Sinai (where God reveals the Ten Commandments to Moses), and their wanderings in the wilderness. The story is one of great hardship and suffering. At first, Moses fails to convince Pharoah to free the Israelites; it is only after God sends 10 plagues (including an infestation of locusts, a hailstorm, and three days of darkness) that Pharoah agrees to Moses’s demands. The Israelites’ escape from Egypt includes the famous parting of the Red Sea and the appearance of God in a storm cloud.

Leviticus (Vayikra)

Vayikra means “And He called” in Hebrew. This book, unlike the previous two, is less focused on narrating the history of the Jewish people. Instead, it deals primarily with priestly matters, offering instructions for rituals, sacrifices, and atonement. These include guidelines for the observance of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, as well as rules for the preparation of food and priestly behavior.

Numbers (Bamidbar)

Bamidbar means “in the desert,” and this book describes the wanderings of the Israelites in the wilderness as they continue their journey toward the promised land in Canaan (the “land of milk and honey”). Moses takes a census of the Israelites and divides the land among the tribes.

Deuteronomy (D’varim)

D’varim means “words” in Hebrew. This is the final book of the Torah. It recounts the end of the Israelites’ journey according to Moses and ends with his death just before they enter the promised land. This book includes three sermons delivered by Moses in which he reminds the Israelites to obey the instructions of God.

Timeline

Scholars believe that the Torah was written and revised by multiple authors over the course of several centuries, with the first full draft appearing in the 7th or 6th century BCE. Various additions and revisions were made over the centuries that followed.

Who Wrote the Torah?

The authorship of the Torah remains unclear. Jewish and Christian tradition state that the text was written by Moses himself (with the exception of the end of Deuteronomy, which tradition states was written by Joshua). Contemporary scholars maintain that the Torah was assembled from a collection of sources by different authors over the course of about 600 years.

Pelaia, Ariela. “What Is the Torah?” Learn Religions, Apr. 17, 2019, learnreligions.com/what-is-the-torah-2076770.

Labour in Marx

Dependent Origination

Article

Christina FeldmanSpring 1999

This article has been excerpted from a program offered by Christina at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies on October 18,1998. Please note that this represents only a small portion of the material offered in the full program.

In the Buddha’s teachings, the second noble truth is not a theory about what happens to somebody else, but is a process which is going on over and over again in our own lives—through all our days, and countless times every single day. This process in Pali is called paṭicca-samuppāda, sometimes translated as “dependent origination” or “co-dependent origination” or “causal interdependence.”

The process of dependent origination is sometimes said to be the heart or the essence of all Buddhist teaching. What is described in the process is the way in which suffering can arise in our lives, and the way in which it can end. That second part is actually quite important.

Paṭicca-samuppāda is said to be the heart of right view or right understanding. It is an understanding that is also the beginning of the eight-fold path, or an understanding that gives rise to a life of wisdom and freedom. The Buddha went on to say that when a noble disciple fully sees the arising and cessation of the world, he or she is said to be endowed with perfect view, with perfect vision—to have attained the true dharma, to possess the knowledge and skill, to have entered the stream of the dharma, to be a noble disciple replete with purifying understanding—one who is at the very door of the deathless. So, this is a challenge for us.

What the paṭicca-samuppāda actually describes is a vision of life or an understanding in which we see the way everything is interconnected—that there is nothing separate, nothing standing alone. Everything effects everything else. We are part of this system. We are part of this process of dependent origination—causal relationships effected by everything that happens around us and, in turn, effecting the kind of world that we all live in inwardly and outwardly.

It is also important to understand that freedom is not found separate from this process. It is not a question of transcending this process to find some other dimension; freedom is found in this very process of which we are a part. And part of that process of understanding what it means to be free depends on understanding inter-connectedness, and using this very process, this very grist of our life, for awakening.

Doctrinally, there are two ways in which this process of paṭicca-samuppāda is approached. In one view it is held to be something taking place over three lifetimes, and this view goes into the issues of rebirth and karma. My own approach today is the second view, which I think is really very vital and alive, which looks at paṭicca-samuppāda as a way of understanding what happens in our own world, inwardly and outwardly, on a moment-to-moment level. It’s about what happens in our heart, what happens in our consciousness, and how the kind of world we experience and live in is actually created every moment.

To me, the significance of this whole description is that if we understand the way our world is created, we also then become a conscious participant in that creation. It describes a process that is occurring over and over again very rapidly within our consciousness. By this time in the day, you have probably all gone throughout countless cycles of dependent origination already. Perhaps you had a moment of despair about what you had for breakfast or what happened on the drive out here, a mind-storm about something that happened yesterday, some sort of anticipation about what might happen today—countless moments that you have gone through where you have experienced an inner world arising: I like this; I don’t like this; the world is like this; this is how it happened; I feel this; I think that.

Already this early in the day, we could track down countless cycles of this process of paṭicca-samuppāda—when we’ve been elated, when we’ve been sad, when we’ve been self-conscious, fearful—we’ve been spinning the wheel. And, it is important to understand this as a wheel, as a process. It is not something static or fixed, not something that stays the same. You need to visualize this as something alive and moving, and we’ll get into how that happens.

The basic principle of dependent origination is simplicity itself. The Buddha described it by saying:

When there is this, that is.

With the arising of this, that arises.

When this is not, neither is that.

With the cessation of this, that ceases.

When all of these cycles of feeling, thought, bodily sensation, all of these cycles of mind and body, action, and movement, are taking place upon a foundation of ignorance—that’s called saṃsāra. That sense of wandering in confusion or blindly from one state of experience to another, one state of reaction to another, one state of contraction to another, without knowing what’s going on, is called saṃsāra.

It’s also helpful, I think, to see that this process of dependent origination happens not only within our individual consciousness, but also on a much bigger scale and on more collective levels—social, political, cultural. Through shared opinions, shared views, shared perceptions or reactions, groups or communities of people can spin the same wheel over extended periods of time. Examples of collective wheel spinning are racism or sexism, or the hierarchy between humans and nature, political systems that conflict, wars—the whole thing where communities or groups of people share in the same delusions. So understanding dependent origination can be transforming not only at an individual level, but it’s an understanding about inter-connectedness that can be truly transforming on a global or universal level. It helps to undo delusion, and it helps to undo the sense of contractedness and the sense of separateness.

In classical presentations, this process of dependent origination is comprised of twelve links. It is important to understand that this is not a linear, progressive, or sequential presentation. It’s a process always in motion and not static at all. It’s also not deterministic. I also don’t think that one link determines the arising of the next link. But rather that the presence of certain factors or certain of these links together provide the conditions in which the other links can manifest, and this is going to become clearer as we use some analogies to describe how this interaction works.

It’s a little bit like a snowstorm—the coming together of a certain temperature, a certain amount of precipitation, a certain amount of wind co-creating a snow storm. Or it’s like the writing of a book: one needs an idea, one needs pen, one needs paper, one needs the ability to write. It’s not necessarily true that first I must have this and then I must have this in a certain sequential order, but rather that the coming together of certain causes and conditions allows this particular phenomenon or this particular experience to be born.

It is also helpful to consider some of the effects of understanding paṭicca-samuppāda. One of the effects is that it helps us to understand that neither our inner world, nor our outer world is a series of aimless accidents. Things don’t just happen. There is a combination of causes and conditions that is necessary for things to happen. This is really important in terms of our inner experience. It is not unusual to have the experience of ending up somewhere, and not knowing how we got there. And feeling quite powerless because of the confusion present in that situation. Understanding how things come together, how they interact, actually removes that sense of powerlessness or that sense of being a victim of life or helplessness. Because if we understand how things come together, we can also begin to understand the way out, how to find another way of being, and realize that life is not random chaos.

Another effect of understanding causes and conditions means accepting the possibility of change. And with acceptance comes another understanding—that with wisdom, we have the capacity to create beneficial and wholesome conditions for beneficial and wholesome results. And that’s the path—an understanding that we have the capacity to make choices in our lives that lead toward happiness, that lead toward freedom and well-being, rather than feeling we’re just pushed by the power of confusion or by the power of our own misunderstanding. This understanding helps to ease a sense of separateness and isolation, and it reduces delusion.

A convenient place to start in order to gain some familiarity with the process of dependent origination is often with the first link of ignorance. This is not necessarily to say that ignorance is the first cause of everything but it’s a convenient starting place:

With ignorance as a causal condition, there are formations of volitional impulses. With the formations as a causal condition, there is the arising of consciousness. With consciousness as a condition, there is the arising of body and mind (nāma-rūpa). With body and mind as a condition, there is the arising of the six sense doors. (In Buddhist teaching, the mind is also one of the sense doors as well as seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching.) With the six sense doors as a condition, there is the arising of contact. With contact as a condition, there is the arising of feeling. With feeling as a condition, there is the arising of craving. With craving as a condition, there’s the arising of clinging. With clinging as a condition, there’s the arising of birth. And, with birth as a condition, there’s the arising of aging and death. That describes the links.

This process, when reversed, is also described as a process of release or freedom. With the abandonment of ignorance, there is the cessation of karmic formations. With the cessation of karmic formations, there is the falling away of consciousness, and so on.

Ignorance (avijjā)

Ignorance is used in Buddhist teachings in a very different way than it is used in our culture. It’s not an insult, or an absence of knowledge—it doesn’t mean we’re dumb. Nonetheless ignorance can be deeply rooted in the consciousness. It may be very invisible to us, and yet it can be exerting its influence in all the ways we think, perceive, and respond. Ignorance is often described as a kind of blindness, of not being conscious in our lives of what is moving us on a moment-to-moment level. Sometimes it is described as perceiving the unsatisfactory to be satisfactory, or as believing the impermanent to be permanent—this is not an unusual experience. Ignorance is sometimes taking that which is not beautiful to be beautiful, as a cause of attachment. Sometimes it is defined as believing in an idea of self to be an enduring and solid entity in our lives when there is no such thing to be found. Or as not seeing things as they actually are, but seeing life, seeing ourselves, seeing other people through a veil of beliefs, opinions, likes, dislikes, projections, clinging, attachments, et cetera, et cetera. Ignorance flavors what kind of speech, thoughts, or actions we actually engage in.

Formations (sankhāra)

Ignorance is the causal condition or climate which allows for the arising of certain kinds of sankhāras—volitional impulses or karmic formations. In a general sense we’re all formations; we’re all sankhāras. Everything that is born and created out of conditions is a formation. Dependent origination gets a little more specific: it talks about intentional actions as body formations, intentional speech as both body and mind formations, and thoughts or states of mind as mental formations. As such it is describing the organization or shaping of our thinking process in accordance with accumulated habits, preferences, opinions. Sankhāras lend a certain fuel to the spinning of the wheel. Within a given cycle, they interact and form more and more of themselves. There is also a constant interaction of the inner and outer, through which the whole cycle keeps getting perpetuated. Some of the formations arise spontaneously in the moment, and some are ways of seeing or ways of reacting that have been built up throughout our whole life. Due to their repetitive use, these sankhāras become somewhat locked or invested in our personality structures and stay close to the surface as more automatic or habitual ways of response. However, it is important to understand that each sankhāra is actually new in every moment. They arise through contact, through certain kinds of stimulation. We tend to think of them as habitual or ever-present because of how we grasp them as something solid. But in our encounter with them in the present moment they are not presented to us as history or as something that is there forever.

Consciousness (viññāṇa)

Formations condition the arising of consciousness. Consciousness is used in the sense of the awareness of all the sensations that enter through the sense doors. So there is the consciousness of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching and thinking. At any given time, one or the other of these sense door consciousnesses dominates our experience. Consciousness also describes the basic climate of the mind at any particular moment—the way it is actually shaped or flavored. So any particular moment might be aversive or dull or greedy, for example, though without interest or intention some of these flavorings of consciousness may not be noticed. Consciousness is also interactive: not only is it shaped by formations and by ignorance, it is also shaping everything going on around us—regardless of whether we pay attention to it or not.

Name and Form (nāma-rūpa)

Consciousness gives rise to nāma-rūpa, which is sometimes translated as mind and body, but that’s a little too simplistic. Rūpa, or body, describes not only our own body but all other bodies and all forms of materiality. Nāma, or mind, describes the feelings, the perceptions, the intentions, the contact, and the kind of attention we give to what appears in the field of our awareness. So nāma describes the whole movement of mind in all its components in relationship to materiality. This is how it works: there’s an arising of rūpa, and then nāma creates concepts or attitudes about it. The kind of relationship we have with any material form, including our own body, is shaped by what’s going on in the mind, whether we are consciously aware of it or not. So the shape of the mind and our body, this nāma-rūpa, is always changing, always moving, never staying the same. Consciousness, body, and mind are always interdependent, with consciousness leading the body and the mind to function in a certain way. If a consciousness has arisen flavored by anger or by greed, by depression, by anxiety—or whatever—it provides the conditions for the body and mind to organize itself in a particular way.

All of the events that have taken place so far in these links of ignorance, karma formations, consciousness, and mind/body—these are actually the most important steps in the generation of karma. These volitional impulses—what is happening in the body and the mind—are actually the generation of karma.

Six-Senses (saḷ-āyatana)

We go on from body and mind to the six sense doors or the six sense spheres, for it is the psychophysical organism that provides us the capacity to see, hear, smell, taste, touch and think. One of the deeper understandings we can have is to acknowledge that the mind is one of the sense-spheres. The thoughts, images and perceptions that arise and pass away in the mind are not so essentially different from the sounds or bodily sensations that come and go in the realm of the senses. We may sometimes have the impression that mind is constant or always “on duty,” but a little bit of a deeper exploration of what happens within the mind actually shatters that perception.

Contact (phassa)

When the sense doors are functioning, contact arises. Contact is this meeting between the sense door and the sense information—I ring the bell, hearing arises. You smell something cooking in the kitchen, the smell arises through the nose sense door. The arising always involves the coming together of the sense door, the sense object and consciousness—the three elements together constitute contact. The Buddha once said that with contact the world arises, and with the cessation of contact there is the cessation of the world. This statement acknowledges the extent to which we create our world of experience by selectively highlighting the data of the senses. Each moment of contact involves isolating an impression out of the vast stream of impressions that are present for us in every moment as we sit here. Contact is what happens when something jumps out of that background and becomes the foreground. When we pay attention to it, there’s a meeting of the sense object and consciousness and the sense door. That is contact.

Feeling (vedanā)

Contact is the foundation or the condition for the arising of feeling. In speaking about feeling here we are not speaking about the more complex emotions such as anger or jealousy or fear or anxiety, but the very fundamental level of feeling impact that is the basis not only of all emotions but of all mind states and responses. We are speaking about the pleasant feeling that arises in connection with what is coming through any of the sense doors; or the unpleasant feeling, or those feelings that are neither pleasant nor unpleasant. This doesn’t mean they are “neutral,” in the sense of a kind of nothingness. Some feelings are certainly there, but they don’t really make a strong enough impression to evoke a pleasant or painful feeling response in us. Actually the impressions and sensations and experiences that are neither pleasant nor unpleasant are some of the more interesting data received by our system.

It is important to acknowledge that the links of contact, of sense doors and feeling that we have been talking about are neither wholesome nor unwholesome in and of themselves; but they become the catalyst of what happens next. The sense doors, the feelings and the contact are the forerunners of how we actually react or respond and how we begin to weave a personal story out of events or impressions that all of us experience at all times. Therefore contact, feeling and sense doors are pretty important places to pay attention.

Craving (taṇhā)

Where does craving come from? From our relationship to feeling; feeling is the condition for craving. This craving is sometimes translated as “unquenchable thirst,” or a kind of appetite that can never be satisfied. Craving begins to be that movement of desire to seek out and sustain the pleasurable contacts with sense objects and to avoid the unpleasant or to make them end. It’s the craving of having and getting, the craving to be or to become someone or something, and the craving to get rid of or to make something end.

Pleasant feelings or impressions are hijacked by the underlying tendency for craving; and unpleasant feelings are hijacked by aversion. And when a feeling is felt as neither pleasant nor unpleasant, it is also hijacked, in this case by the deluded tendency to dismiss it from our consciousness and say it doesn’t matter. Our sense of self finds it very hard to have an identity with any impression or sensation which is neither pleasant nor unpleasant.

It is at the point where craving arises in response to pleasant or unpleasant feeling that our responses become very complex, and we run into a world of struggle. When we crave for something, we in a way delegate authority to an object or to an experience or to a person, and at the same time we are depriving ourselves of that authority. As a result, our sense of well-being, our sense of contentment or freedom, comes to be dependent upon what we get or don’t get. You all know that kind of restlessness of appetite—there’s never enough; just one more thing is needed; one more experience, one more mind state, one more object, one more emotion, and then I’ll be happy.

What we don’t always see through when we are in the midst of ignorance is that the way such promise is projected, externalized, or objectified is actually something which always leaves us with a sense of frustration. We are dealing here with a very basic hunger, and we allow our world to be organized according to this hunger by projecting the power to please or threaten onto other things. But the important thing to remember is that craving is also a kind of moment-to-moment experience; it arises and it passes.

Clinging (upādāna)

Craving and clinging (also called grasping), are very close together. Craving has a certain momentum, a certain one-way direction, and when it become intense, it becomes clinging. Now, one way that craving becomes clinging is that very fixed positions are taken; things become good or bad; they become worthy or unworthy; they become valuable or valueless. And the world is organized into friends and enemies, into opponents and allies according to what we are attached to or what we grasp or get hold of. That sense of becoming fixed reinforces and solidifies the values we project onto experience or objects. But it also reinforces belief systems and opinions, and the faculty of grasping holds on to of images of self. “I am like this.” “I need this.” “I need to get rid of this,” and so on. And, often, many things in this world are evaluated according to their perceived potential to satisfy our desires. What all this does is actually make us very busy. Think about the situations when you really want something, how much activity starts to be generated in terms of thinking and plotting and planning and strategizing: you know, the fastest route to get there from here, the most direct route to make this happen.

Traditionally, clinging is often broken down into four different ways in which we can make ourselves suffer. There is the clinging to sensuality or sense objects. The other side of clinging to sense objects is clinging to views, theories, opinions, beliefs, philosophies—they become part of ourselves. Another form that grasping takes is clinging to certain rules—the belief that if I do this, I get this. Or one says, “This is my path. This is going to take me from here to there.” The last of the forms of clinging Buddha talked about was clinging to the notion of “I am”— the craving to be someone, and the craving not to be someone, dependent on clinging to an idea and an ideal of self. This notion of self is perhaps the most delusionary force in our lives.

Becoming (bhava)

Clinging is followed by becoming or arising—the entire process of fixing or positioning the sense of self in a particular state of experience. Any time we think in self-referential terms, “I am,” “I am angry,” “I am loving,” “I am greedy,” ” I know,” “I’m this kind of person” and so on, an entire complex of behavior is generated to serve craving and clinging. I see something over there that I’ve projected as “This is going to make me really happy if I get this,” and I organize my behavior, my actions, my attention in order to find union with that. This is the process of becoming—becoming someone or something other than what is.

Birth (jāti)

Birth, the next link in the chain of dependent origination, is the moment of arrival. We think “I think I got it!” “I found it (the union with this image or role or identity or sensation or object),” “I am now this”—the emergence of an identity, a sense of self that rests upon identifying with a state of experience or mode of conduct, the doer, the thinker, the seer, the knower, the experience, the sufferer—this is what birth is. And there is a resulting sense of that birth, of one who enjoys, one who suffers, one who occupies, one who has all the responsibility of that birth.

Aging and Death (jarā-maraṇa)

Birth is followed by death in which there is the sense of loss, change, the passing away of that state of experience. “I used to be happy.” “I used to be successful.” “I was content in the last moment.” And so on. The passing away of that state of experience, the feeling of being deprived or separated from the identity, “I used to be…” is the moment of death. In that moment of death, we sense a loss of good meditation experience, the good emotional experience. We say it’s gone. And associated with that sense is the pain and the grief, the despair of our loss.

These different factors interact to create certain kinds of experiences in our lives. What is important to remember is that none of this is predetermined. Just like the climate for snow, the presence of certain of these links is going to allow other experiences to happen. Not that they must happen, or definitely will happen, but they allow for certain experiences to happen. This may sound like bad news in the beginning, but we get to the good news later.

The second noble truth of dependent origination describes a process that happens every single moment of our lives. But clearly there is a distinction between a process and a path, and it is an absolutely critical distinction. One doesn’t actually want to continue in life just as a spectator, watching the same process happening over and over and over again—a spectator of our own disasters. Awareness is actually something a bit more than simply seeing a process take place. In choosing to be aware, we make a leap which is really about an application of a path in our lives, otherwise mere seeing of the process becomes circular and we continue to circle around. The path is what actually takes us out into a different process.

Now, the third noble truth [the cessation of suffering] is not a value judgment in itself; it is simply a portrayal of the way in which it is possible to step off a sense of being bound to this wheel of saṃsāra or to the links of dependent origination. It is significant to remember that it doesn’t have to be any one link that we step off or that there is only one place where we can get out of this maze. In fact, we can step out of the maze and into something else at any of the links.

The well-known Thai meditation master Buddhādasa Bhikkhu describes the path out of suffering as “the radiant wheel.” It is also called the wheel of understanding or the wheel of awakening, in which the fuel of greed, anger, and delusion which give us the feeling of being bound to the wheel of saṃsāra, is replaced by the fuel of wise reflection, ethics, and faith.

One portrayal of the alternate wheel is that wise reflection, ethics, and faith lead to gladness of heart and mind, the absence of dwelling in contractedness and proliferation. The gladness is in itself a condition for rapture, a falling in love with awareness. The rapture is a condition for calmness and calmness is a condition for happiness. Happiness is a condition for concentration; concentration is a condition for insight; insight is a condition for disenchantment or letting go, and letting go is a condition for equanimity, the capacity to separate the sense of self from states of experience so that an experience can be just an experience rather than be flavored by an “I am”-ness of a self. And equanimity in itself is a condition for liberation and the end of suffering.

Paticca-samuppada

Paticca-samuppada

Buddhism Written By:

See Article HistoryAlternative Titles: conditioned genesis, law of dependent origination, pratitya-samutpada

Paticca-samuppada, (Pali: “dependent origination”) Sanskrit pratitya-samutpada, the chain, or law, of dependent origination, or the chain of causation—a fundamental concept of Buddhism describing the causes of suffering (dukkha; Sanskrit duhkha) and the course of events that lead a being through rebirth, old age, and death.

Existence is seen as an interrelated flux of phenomenal events, material and psychical, without any real, permanent, independent existence of their own. These events happen in a series, one interrelating group of events producing another. The series is usually described as a chain of 12 links (nidanas, “causes”), though some texts abridge these to 10, 9, 5, or 3. The first two stages are related to the past (or previous life) and explain the present, the next eight belong to the present, and the last two represent the future as determined by the past and what is happening in the present. The series consists of: (1) ignorance (avijja; avidya), specifically ignorance of the Four Noble Truths, of the nature of humanity, of transmigration, and of nirvana; which leads to (2) faulty thought-constructions about reality (sankhara; samskara). These in turn provide the structure of (3) knowledge (vinnana; vijnana), the object of which is (4) name and form—i.e., the principle of individual identity (nama–rupa) and the sensory perception of an object—which are accomplished through (5) the six domains (ayatana; shadayatana)—i.e., the five senses and their objects—and the mind as the coordinating organ of sense impressions. The presence of objects and senses leads to (6) contact (phassa; sparsha) between the two, which provides (7) sensation (vedana). Because this sensation is agreeable, it gives rise to (8) thirst (tanha; trishna) and in turn to (9) grasping (upadana), as of sexual partners. This sets in motion (10) the process of becoming (bhava; bjava), which fructifies in (11) birth (jati) of the individual and hence to (12) old age and death (jara-marana; jaramaranam).

The formula is repeated frequently in early Buddhist texts, either in direct order (anuloma) as above, in reverse order (pratiloma), or in negative order (e.g., “What is it that brings about the cessation of death? The cessation of birth”). Gautama Buddha is said to have reflected on the series just prior to his enlightenment, and a right understanding of the causes of pain and the cycle of rebirth leads to emancipation from the chain’s bondage.

The formula led to much discussion within the various schools of early Buddhism. Later, it came to be pictured as the outer rim of the wheel of becoming (bhavachakka; bhavachakra), frequently reproduced in Tibetan painting.

This article was most recently revised and updated by Matt Stefon, Assistant Editor.

Namarupa

Namarupa, aka: Nāmarūpa, Nama-rupa; 7 Definition(s)

Introduction

Namarupa means something in Buddhism, Pali, Hinduism, Sanskrit, Marathi. If you want to know the exact meaning, history, etymology or English translation of this term then check out the descriptions on this page. Add your comment or reference to a book if you want to contribute to this summary article.

In Hinduism

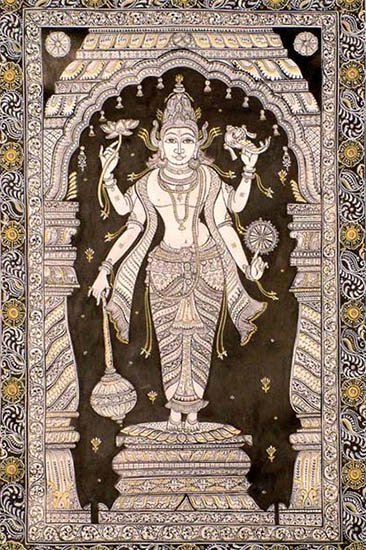

Shilpashastra (iconography)

Shilpashastra > glossary [N] [Namarupa in Shilpashastra glossaries] « previous · next »

Nāmarūpa (नामरूप):—The universe of our empirical experience is composed of Ideation (nāma) and Form (rūpa). We see the universe and then participate in it through the process of naming everything. By naming something we are able to understand it and obtain a sense of control over it. So this process of creating, cognising and naming are all symbolised by the drum (ḍamaru), held in the right upper hand of Naṭarāja (a dancing form of Śiva).(Source): Red Zambala: Hindu Icons and Symbols | Trinity

context information

Shilpashastra (शिल्पशास्त्र, śilpaśāstra) represents the ancient Indian science (shastra) of creative arts (shilpa) such as sculpture, iconography and painting. Closely related to Vastushastra (architecture), they often share the same literature.

Discover the meaning of namarupa in the context of Shilpashastra from relevant books on Exotic India

In Buddhism

Theravada (major branch of Buddhism)

Theravada > glossary [N] [Namarupa in Theravada glossaries] « previous · next »

Name and form; mind and matter; mentality physicality. The union of mental phenomena (nama) and physical phenomena (rupa) that constitutes the five aggregates (khandha), and which lies at a crucial link in the causal chain of dependent co arising (paticca samuppada).(Source): Access to Insight: A Glossary of Pali and Buddhist Terms

(lit. ‘name and form’): ‘mind-and-body’, mentality and corporeality. It is the 4th link in the dependent origination (s. paticcasamuppāda 3, 4) where it is conditioned by consciousness, and on its part is the condition of the sixfold sense-base. In two texts (D. 14, 15), which contain variations of the dependent origination, the mutual conditioning of consciousness and mind-and-body is described (see also S. XII, 67), and the latter is said to be a condition of sense-impression (phassa); so also in Sn. 872.

The third of the seven purifications (s. visuddhi), the purification of views, is defined in Vis.M. XVIII as the “correct seeing of mind-and-body,” and various methods for the discernment of mind-and-body by way of insight-meditation (vipassanā, q.v.) are given there. In this context, ‘mind’ (nāma) comprises all four mental groups, including consciousness. – See nāma.

In five-group-existence (pañca-vokāra-bhava, q.v.), mind-and body are inseparable and interdependent; and this has been illustrated by comparing them with two sheaves of reeds propped against each other: when one falls the other will fall, too; and with a blind man with stout legs, carrying on his shoulders a lame cripple with keen eye-sight: only by mutual assistance can they move about efficiently (s. Vis.M. XVIII, 32ff). On their mutual dependence, see also paticca-samuppāda (3).

With regard to the impersonality and dependent nature of mind and corporeality it is said:

“Sound is not a thing that dwells inside the conch-shell and comes out from time to time, but due to both, the conch-shell and the man that blows it, sound comes to arise: Just so, due to the presence of vitality, heat and consciousness, this body may execute the acts of going, standing, sitting and lying down, and the 5 sense-organs and the mind may perform their various functions” (D. 23).

“Just as a wooden puppet though unsubstantial, lifeless and inactive may by means of pulling strings be made to move about, stand up, and appear full of life and activity; just so are mind and body, as such, something empty, lifeless and inactive; but by means of their mutual working together, this mental and bodily combination may move about, stand up, and appear full of life and activity.”(Source): Pali Kanon: Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrinescontext information

Theravāda is a major branch of Buddhism having the the Pali canon (tipitaka) as their canonical literature, which includes the vinaya-pitaka (monastic rules), the sutta-pitaka (Buddhist sermons) and the abhidhamma-pitaka (philosophy and psychology).

Discover the meaning of namarupa in the context of Theravada from relevant books on Exotic India

Mahayana (major branch of Buddhism)

Mahayana > glossary [N] [Namarupa in Mahayana glossaries] « previous · next »

Nāmarūpa (नामरूप, “Name-and-form”) refers to the fourth of twelve pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination) according to the Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra chapter X. Vijñāna produces both the four formless aggregates (arūpiskandha) [perception (saṃjñā), feeling (vedanā), volition (saṃskāra), consciousness (vijñāna)] and form (rūpa) which serves as base them. This is name and form, nāmarūpa. From this nāmarūpa there arise the six sense organs, eye (cakṣus), etc. These are the ṣaḍāyatanas, the six inner bases of consciousness.(Source): Wisdom Library: Maha Prajnaparamita Sastra

context information

Mahayana (महायान, mahāyāna) is a major branch of Buddhism focusing on the path of a Bodhisattva (spiritual aspirants/ enlightened beings). Extant literature is vast and primarely composed in the Sanskrit language. There are many sūtras of which some of the earliest are the various Prajñāpāramitā sūtras.

Discover the meaning of namarupa in the context of Mahayana from relevant books on Exotic India

General definition (in Buddhism)

Buddhism > glossary [N] [Namarupa in Buddhism glossaries] « previous · next »

Nāmarūpa (नामरूप) refers to “name and bodily-form” and represents the fourth of the “twelve factors of conditional origination” (pratītyasamutpāda) as defined in the Dharma-saṃgraha (section 42). The Dharma-samgraha (Dharmasangraha) is an extensive glossary of Buddhist technical terms in Sanskrit (eg., nāmarūpa). The work is attributed to Nagarjuna who lived around the 2nd century A.D.(Source): Wisdom Library: Dharma-samgraha

Languages of India and abroad

Marathi-English dictionary

Marathi > glossary [N] [Namarupa in Marathi glossaries] « previous · next »

nāmarūpa (नामरूप).—n (S) Name and repute &c. See nāṃvarūpa.(Source): DDSA: The Molesworth Marathi and English Dictionary

nāmarūpa (नामरूप).—n Name and form.(Source): DDSA: The Aryabhusan school dictionary, Marathi-Englishcontext information

Marathi is an Indo-European language having over 70 million native speakers people in (predominantly) Maharashtra India. Marathi, like many other Indo-Aryan languages, evolved from early forms of Prakrit, which itself is a subset of Sanskrit, one of the most ancient languages of the world.

Discover the meaning of namarupa in the context of Marathi from relevant books on Exotic India

Relevant definitions

Search found 1227 related definition(s) that might help you understand this better. Below you will find the 15 most relevant articles:

| Rupa | Rūpa (रूप) represents one of the four stages of creation corresponding to the Ājñā-cakra, and i… | |

| Nama | Nāma (नाम) refers to “nouns and pronouns” and represents one of the four classes of words accor… | |

| Kamarupa | Kāmarūpa (कामरूप).—a. 1) taking any form at will; जानामि त्वां प्रकृतिपुरुषं कामरूपं मघोनः (jān… | |

| Surupa | Surūpā (सुरूपा).—A daughter of Viśvakarman. Priyavrata, son of Svāyambhuva Manu married Surūpā … | |

| Vishvarupa | Viśvarūpa (विश्वरूप) refers to one of the various Vibhava manifestations according to the Īśvar… | |

| Bahurupa | Bahurūpa (बहुरूप) is the name of a sacred spot mentioned in the Nīlamatapurāṇa.—Bahurūpa is rec… | |

| Svarupa | Svarūpa (स्वरूप).—An asura. This asura remains in the palace of Varuṇa and serves him. (Sabhā P… | |

| Shatarupa | Śatarūpā (शतरूपा).—Wife of Svāyambhuva Manu, who took his sister Śatarūpā herself as his wife. … | |

| Purvarupa | Pūrvarūpa (पूर्वरूप) is another name for Pūrvarūpatā: one of the 93 alaṃkāras (“figures of spee… | |

| Jatarupa | Jātarūpa (जातरूप).—a. beautiful, brilliant. (-pam) 1 gold; पुनश्च याचमानाय जातरूपमदात् प्रभुः (… | |

| Ekarupa | Ekarūpa (एकरूप) refers to one of the 135 metres (chandas) mentioned by Nañjuṇḍa (1794-1868 C.E…. | |

| Sukharupa | Sukharūpa (सुखरूप).—a. having an agreeable appearance. Sukharūpa is a Sanskrit compound consist… | |

| Rupavali | Rūpāvalī (रूपावली).—a list or series of variations of grammatical forms. Rūpāvalī is a Sanskrit… | |

| Rupadhatu | Rūpadhātu (रूपधातु) refers to the “gods of the form realm” according to the “world of transmigr… | |

| Kurupa | Kurūpa (कुरूप).—a. ugly, deformed; कुपुत्रोऽपि भवेत्पुंसां हृदयानन्दकारकः । दुर्विनीतः कुरूपोऽप… |

Relevant text

Search found 48 books and stories containing Namarupa, Nāmarūpa or Nama-rupa. You can also click to the full overview containing English textual excerpts. Below are direct links for the most relevant articles:

The Doctrine of Paticcasamuppada (by U Than Daing)

Chapter 2 – Sections, Links, Factors And Periods

Chapter 1 – What Is Paticcasamuppada?

Chapter 9 – The Circling Of Paticcasamuppada

+ 5 more chapters / show preview

A Discourse on Paticcasamuppada (by Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw)

Chapter 4 – Ignorance And Illusion < [Part 2]

Chapter 3 – Anuloma Reasoning < [Part 1]

Chapter 7 – From Vinnana Arises Nama-rupa < [Part 3]

+ 43 more chapters / show preview

A History of Indian Philosophy Volume 1 (by Surendranath Dasgupta)

Part 4 – The Doctrine of Causal Connection of early Buddhism < [Chapter V – Buddhist Philosophy]

Part 6 – The Fundamental Ideas of Jaina Ontology < [Chapter VI – The Jaina Philosophy]

Part 5 – The Khandhas < [Chapter V – Buddhist Philosophy]

+ 3 more chapters / show preview

Fundamentals of Vipassana Meditation (by Venerable Mahāsi Sayādaw)

Abhidhamma in Daily Life (by Ashin Janakabhivamsa) (by Ashin Janakabhivamsa)

Part 6 – What Is Nibbána? < [Chapter 11 – Planes Of Existence]

Cetasikas (by Nina van Gorkom)

Appendix 9 – The Stages Of Insight < [Appendix And Glossary]

Chapter 35 – The Stages Of Insight < [Part IV – Beautiful Cetasikas]

Click here for all 48 books Item last updated: 19 November, 2018 wisdomlib – the greatest source of ancient and modern knowledge;

info@wisdomlib.org | contact form | privacy policy

Arguments for and against the Existence of God

The polytheistic conceptions of God were criticized and derided by the monotheistic religions. Since the Enlightenment, monotheistic concepts have also come under criticism from atheism and pantheism.

Arguments for the Existence of God

Philosophers have tried to provide rational proofs of God’s existence that go beyond dogmatic assertion or appeal to ancient scripture. The major proofs, with their corresponding objections, are as follows:

1. Ontological: It is possible to imagine a perfect being. Such a being could not be perfect unless its essence included existence. Therefore a perfect being must exist.

Objection: You cannot define or imagine a thing into existence.

2. Causal: Everything must have a cause. It is impossible to continue backwards to infinity with causes, therefore there must have been a first cause which was not conditioned by any other cause. That cause must be God.

Objections: If you allow one thing to exist without cause, you contradict your own premise. And if you do, there is no reason why the universe should not be the one thing that exists or originates without cause.

3. Design: Animals, plants and planets show clear signs of being designed for specific ends, therefore there must have been a designer.

Objection: The principles of self-organization and evolution provide complete explanations for apparent design.

3a. Modern design argument: the Anthropic Cosmological Principle. This is the strongest card in the theist hand. The laws of the universe seem to have been framed in such a way that stars and planets will form and life can emerge. Many constants of nature appear to be very finely tuned for this, and the odds against this happening by chance are astronomical.

Objections: The odds against all possible universes are equally astronomical, yet one of them must be the actual universe. Moreover, if there are very many universes, then some of these will contain the possibility of life. Even if valid, the anthropic cosmological principle guarantees only that stars and planets and life will emerge – not intelligent life. In its weak form, the anthropic cosmological principle merely states that if we are here to observe the universe, it follows that the universe must have properties that permit intelligent life to emerge.

4. Experiential: A very large number of people claim to have personal religious experiences of God.

Objections: We cannot assume that everything imagined in mental experiences (which include dreams, hallucinations etc) actually exists. Such experiences cannot be repeated, tested or publicly verified. Mystical and other personal experiences can be explained by other causes.

5. Pragmatic: Human societies require ethics to survive. Ethics are more effectively enforced if people fear God and Hell and hope for Heaven (cf. the origin of ethical systems).

Objections: The usefulness of a belief does not prove its truth. In any case, many societies have thrived without these beliefs, while crime has thrived in theistic societies believing in heaven and hell.

General objection against all the rational proofs for God:

Each of the above arguments is independent of the others and

cannot logically be used to reinforce the others.

The cause argument – even if it were valid – would prove only a first

cause. It would tell us nothing about the nature of that cause, nor

whether the cause was mental or physical. It would not prove that the

first cause was the personal, judging, forgiving God of Judaism,

Christianity, or Islam. It would not prove the existence of a

designer or of a perfect being. Equally, the design argument would

prove only a designer, the ontological argument would prove only the

existence of a perfect being, and so on. None of these arguments

individually can prove that the cause, designer or perfect being were

one and the same – they could be three different beings.

Arguments against the existence of God

The major philosophical criticisms of God as viewed by Judaism, Christianity and Islam are as follows:

1. Evil: Because evil exists, God cannot be all-powerful. all-knowing and loving and good at the same time.

2. Pain: Because God allows pain, disease and natural disasters to exist, he cannot be all-powerful and also loving and good in the human sense of these words.

3. Injustice: Destinies are not allocated on the basis of merit or equality. They are allocated either arbitrarily, or on the principle of “to him who has, shall be given, and from him who has not shall be taken even that which he has.” It follows that God cannot be all-powerful and all-knowing and also just in the human sense of the word.

4. Multiplicity: Since the Gods of various religions differ widely in their characteristics, only one of these religions, or none, can be right about God.

5. Simplicity: Since God is invisible, and the universe is no different than if he did not exist, it is simpler to assume he does not exist (see Occam’s Razor).

None of these criticisms apply to the God of pantheism, which is identical with the universe and nature.

See also: Has Science Found God?: Examining the Evidence from Modern Physics and Cosmology

Copyright© 1997 Principia Cybernetica – Referencing this page

pāramī, pāramitā

pāramī, pāramitā: Perfection of the character. A group of ten qualities developed over many lifetimes by a bodhisatta, which appear as a group in the Pali canon only in the Jataka (“Birth Stories”): generosity (dāna), virtue (sīla), renunciation (απάρνηση) (nekkhamma), discernment (paññā), energy/persistence (viriya), patience/forbearance (khanti), truthfulness (sacca), determination (adhiṭṭhāna), good will (καλή θέληση) (mettā), and equanimity (γαλήνη) (upekkhā).

discernment: the ability to judge well.

persistence: the continued or prolonged existence of something

forbearance: patient self-control; restraint and tolerance